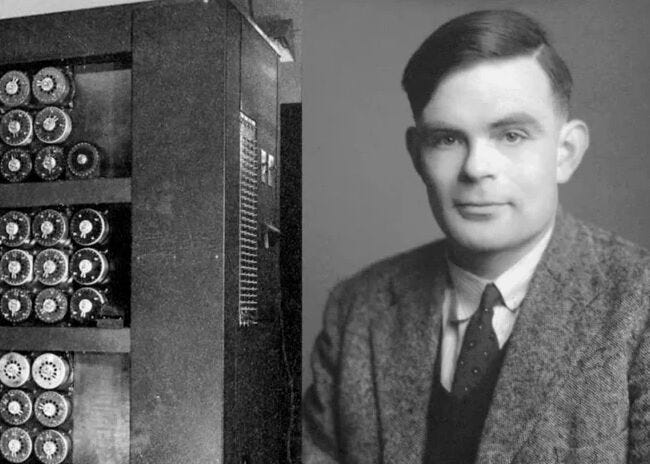

In March 2025, a study out of UC San Diego made history. For the first time, a machine (OpenAI’s GPT-4.5) passed the original version of the Turing test. Not the simplified version often invoked in media headlines, but the real thing: Turing’s three-player “imitation game,” where human judges converse simultaneously with on…

Substack is the home for great culture